Bentley Boys: Glorious chapter in British motor racing history

Source: MotorSport.com

It is true that without the cars there would have been no "Bentley Boys"; but it is equally true that the "Bentley Boys" lent excitement, drama and prestige to the Cricklewood Bentley. Hard driving on the track, they played hard in their leisure time. They were amateurs of the old school, gifted sportsmen who competed not for monetary reward, but out of bravado and the thrill of the chase.

WO himself said that: "The company's activities, particularly in its racing, attracted the public's fancy and added a touch of colour, vicarious glamour and excitement to drab lives." Unlike modern racing drivers, the Bentley Boys weren't highly paid professionals.

The first of the "Bentley Boys" was John Duff. Duff was atypical in that he was not particularly wealthy, and he raced Bentleys at Brooklands and Le Mans with an eye to building up his car dealership. What was characteristic about Duff was his courage and endurance. He drove a 3 Litre single-handedly for two consecutive days at Brooklands in 1922, averaging just under 90 mph. He and Clement, then head of Bentley's experimental and racing shops and a talented development and racing driver, finished fourth in the same car at Le Mans in 1923. In 1924, Duff and Clement won the race, again in a 3 Litre. Duff went on to set the World's 24 hour record at 95.03 mph with Barnato as his co-driver at Montlhery.

More in the mould was Dr Dudley 'Benjy' Benjafield, a Harley Street physician and bacteriologist. In 1925 Benjy drove a 3 Litre at Le Mans, thereafter driving for either the works team or the Birkin Blower team in every year up to 1930.

Benjy was a true amateur and drove for fun, deriving an enormous amount of satisfaction from his racing. Off the track he participated to the full in the parties and the fun and games.

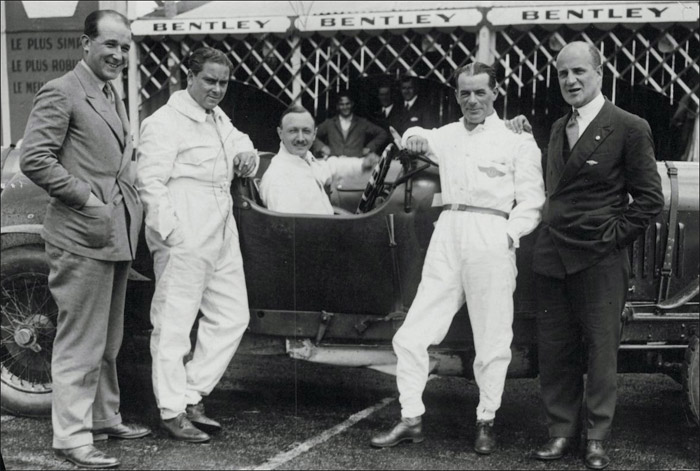

Frank Clement, Benjafield and Bertie Kensington Moir, an experienced driver who at that date managed Bentley's service department, and Sammy Davies, The Autocar's sports editor, formed the nucleus of the "Bentley Boys". In 1925/6 they - and Bentley Motors - were joined by the man largely responsible for making it all happen. Woolf Barnato. Barnato was persuaded by WO to buy into the company, taking a majority shareholding and the chairmanship. With Barnato at the helm, and money in the coffers, Bentley Motors went motor racing wholeheartedly, and the legend of the great green Bentleys and the "Bentley Boys" took off in the public imagination.

Barnato's prodigious wealth originated from South African diamonds. A gifted all-round athlete, Barnato excelled at motor racing as he excelled at every other sport he took up. He also lived life to the full, throwing outside parties at Ardenrun, his house in Lingfield, Surrey, spending much of the summer in the south of France, sailing and generally enjoying his great wealth. Barnato won Le Mans three years in a row - 1928, 1929, and 1930. He also won the 1929 Six Hours and the 1930 Double Twelve, both at Brooklands.

In 1927, the company's racing programme came of age, and with it the "Bentley Boys" arrived as a recognisable entity with an esprit de corps all of their own.

Tim Birkin is still regarded by many as the greatest British driver of his day. His money derived from the lace business. Intense and restless, like many of his generation Birkin found the post-war world dull and lacking in excitement. He found his metier behind the wheel of racing cars, particularly Bentleys. Birkin drove his 4½ Litre at Brooklands, in Ireland, France and Germany in 1928, before hitting on the idea of supercharging it. Thus was born the legendary Blower Bentley, one of the most charismatic sports/racing cars ever made.

"He lived equally furiously off the track, his fondness for the dramatic having surprising and often excruciatingly funny results. Life was never dull with Tim around, if only because of the abundance and wide variety of his girlfriends". (WO). Birkin's life was indeed dramatic, but correspondingly short, he died in 1933 after the Tripoli Grand Prix, probably from malarial poisoning.

Benjafield and Davis won in their 3 Litre, despite crash damage in an incident at White House that put the new 4½ Litre and a second 3 Litre driven by champion jockey George Duller and Baron d'Erlanger, international banker and playboy, out of the race. The combination of Duller's slapstick humour and d'Erlanger's imperturbable wit and dry humour left a deep impression on WO.

Again immensely wealthy, Bentley Boy Bernard Rubin derived his money from farming and pearling interests in Western Australia. Rubin was principally Barnato's friend, and he was thus invited to share the prototype 4½ Litre "Old Mother Gun" with Barnato in the 1928 Le Mans race. They won a nerve-wracking race, the chassis frame of their car cracking on the last lap, pulling out the top water hose and draining the radiator. Barnato nursed "Old Mother Gun" over the line with a red-hot engine, the temperature gauge needle off the scale. Rubin again drove purely for the sport, but after rolling his car in the 1929 TT Glen Hill, he evidently decided that motor racing was just too dangerous. Rubin scarcely out lived Birkin, losing his life in a flying accident in 1934.

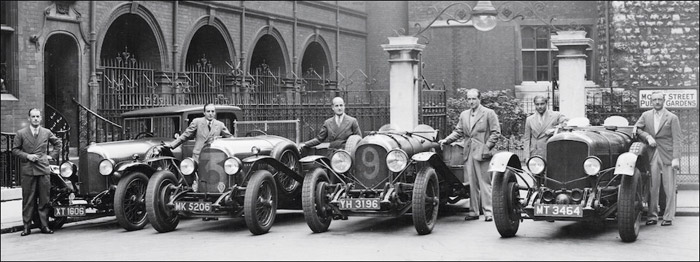

In 1929, with the new 6½ Litre Speed Six in race trim, Bentleys could do no wrong. It proved to be powerful, fast, and reliable, good qualities for the sort of endurance racing at which Bentleys excelled. Bentleys took the first four places at Le Mans in that year, Barnato and Birkin in the Speed Six leading from start to finish, heading up three 4½ Litres in the next three places. Alongside the familiar faces, the second placed 4½ Litre was driven by Jack Dunfee and Glen Kidston. Jack Dunfee, along with his younger brother Clive, drove for the works and the Birkin teams. The brothers competed until 1932, the year in which Clive was killed at Brooklands in the 500, driving the very fast 8 Litre engined "Old Number One" in outer circuit track form.

Kidston was a submarine officer in the Great War, and proved to be fast and utterly fearless behind the wheel. WO describes him as "a born adventurer, rough, tough, sharp, and as fearless as Birkin...Birkin, Barnato, Rubin and Kidston (were) la crème de la crème of the Bentley Boys". Kidston's life was punctuated by incident. His submarine became trapped in mud on the seabed, and was written off as lost before it finally surfaced. He was the sole survivor of a plane crash, fighting his way through the fuselage of the crashed London-Paris airliner on which he was travelling. He crashed in the 1929 TT, and again in the 1930 Monte Carlo rally; he nevertheless continued after having the front brake drums removed and the front brakes disconnected! Kidston's luck ran out in 1931 when his De Havilland Moth broke up in the air over Africa.

In 1930, the Works entered two Speed Sixes for the Double Twelve, as preparation for Le Mans, and finished first and second. At Le Mans that year, the three Works Speed Sixes were entered. The Barnato/Kidston car finished first, the Clement/Watney car second; the third car crashed. Birkin entered three Blowers, one was a non-starter, the other two didn't finish. And that was pretty much the end. After Le Mans, Bentley Motors retired from motor racing, Barnato simultaneously announcing his retirement. The Birkin team continued for the rest of the 1930 season, but disbanded thereafter.

So ended a brief but glorious chapter in British motor racing history, just four seasons in which the legend was made. The "Bentley Boys" lie at the heart of this legend. In WO's words, "The public liked to imagine them living in expensive Mayfair flats with several mistresses and, of course, several very fast Bentleys, drinking champagne in night clubs, playing the horses and the Stock Exchange, and beating furiously around racing tracks at the weekend. Of at least several of them this was not such an inaccurate picture". The Cricklewood Bentley fitted the mould perfectly.